“Sleep is the most moronic fraternity in the world, with the heaviest dues and the crudest rituals.”

~Vladimir Nabokov

“Sleep is the most moronic fraternity in the world, with the heaviest dues and the crudest rituals.”

~Vladimir Nabokov

In Sleep Medicine, we use the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD) 3, to define insomnia as:

“A persistent difficulty with sleep initiation, duration, consolidation, or quality that occurs despite adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep, and results in some form of daytime impairment.”

When we see insomnia in

younger infants and children, in the absence of a neurodevelopmental challenge (and even sometimes in kids with such challenges), the problem is almost always

behavioral insomnia of childhood sleep onset association type. In this disorder, the child simply cannot soothe herself/himself to sleep without outside intervention (a parent, a bottle, a particular toy, etc.). The mechanism to fix this disorder is very simple - teach the child to fall asleep independent of any outside influence. The mechanics of how to do this require a highly personalized, precision management strategy tailored to the situation.

In older children and adults, insomnia typically shows up in three flavors:

Some have a Neapolitan version with a blend of all three flavors.

Older versions of the ICSD described subtypes of insomnia, which while rare to see in a pure form, are useful for discussion purposes.

These subtypes include:

Psychophysiological insomnia: characterized by heightened arousal and learned sleep-prevention associations. These individuals often sleep terribly at home, but fall asleep easily somewhere else or when they are not trying to sleep. If you read about insomnia, and if you are reading this blog in the middle of the night while trying to fall back to sleep, you might have run across the insomnia strategy of instead of trying to fall asleep, try to stay awake. That notion comes from this insomnia subtype.

Idiopathic insomnia:

characterized by long standing complaints of sleep difficulties with onsets in early childhood lasting into adulthood. Broadly speaking, these individuals likely have some congenital issue with some loss of function mutation involving neurons in the anterior hypothalamus, the so called ventrolateral preoptic area (VLPO) or some gain of function involving neurons in the ascending arousal system in the brainstem - see blog on sleep state switching.

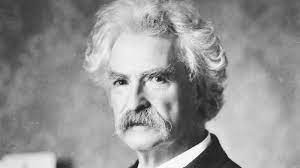

I suspect Mark Twain had this as he spoke often of sleep and once said:

“I realize that from the cradle up I have been like the rest of the race- never quite sane in the night.”

Paradoxical insomnia: used to be called sleep state misperception - a term I prefer as it defines the condition better. The issue here is that individuals complain of poor sleep, but there is no corroborative evidence of such a disturbance noted on actigraphy, sleep logs or polysomnography. These individuals simply underestimate how much sleep they get on a regular basis.

Inadequate sleep habits:

I changed the name from inadequate sleep hygiene in accordance with what I have alluded to in prior blogs that no one wants to hear someone talk about their hygiene. These individuals usually have trouble sleeping at night because they sleep during the day, keep odd sleep hours, lack a routine, use sleep disrupting products like caffeine, tobacco and alcohol close to bed or engage in physical or emotional activities too close to bedtime. These individuals also tend to use their room and their bed for activities other than sleep.

Another useful term that this newer edition of the ICSD mentions, but does not classify as a subtype is

insomnia due to a medical or mental disorder. This is just as it sounds, for example someone with bipolar disorder, in a manic cycle who cannot sleep or someone with hyperthyroidism who cannot sleep. This is a diagnosis that applies in particular to those with neurodevelopmental disabilities like autism where their sleep is disrupted because of their autism (the medical condition).

It can be difficult to distinguish between these subtypes, but I have found patients and families often learn from or gain some self reflection upon hearing these definitions and it makes them feel less alone in their diagnosis to know that in a broad sense, what they are experiencing, while unique for her/him, is not as isolating as it might seem.

Remember, you are not alone in your experience - and we are here to help.

To read more about insomnia, visit:

www.sleepeducation.org